Summary

- Indonesia sealed a US$20 billion deal in the world's largest climate finance commitment for energy transition under the JETP program.

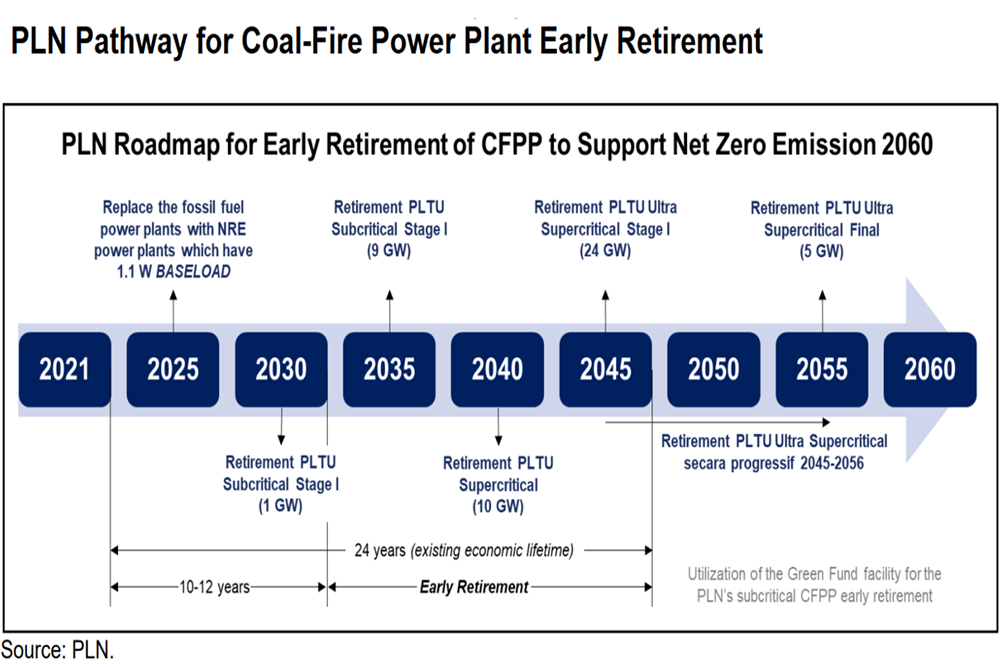

- The government pledged to retire all coal-fired power plants by 2030 and replace them with renewable energy before obtaining funding.

- Many loopholes and constraints exist so that Indonesia or donor countries can backslide from commitments, and funding deals may be revised.

Issue

Indonesia sealed a US$20 billion deal for energy transition through the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) from developed countries in the International Partners Group (IPG) for the next 3-5 years. This fund supports the clean energy transition by reducing emissions in the electricity sector and developing and increasing renewable energy.

This amount is the largest climate finance commitment for a developing country. Previously, IPG had launched its US$8.5 billion inaugural JETP partnership with South Africa, which was announced at COP26 in Glasgow last year.

Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan said the Indonesian government would lead the preparation of an investment action plan under this funding scheme. "We will maximize the platform managed by PT SMI [Sarana Multi Infrastruktur]," he said at a press conference at the Bali International Convention Center (BICC) on Tuesday (11/15).

Indonesia has raised its emission reduction target in the Enhanced National Determined Contribution (NDC) document from 29 percent to 31.8 percent in 2030 with self-efforts and 43.2 percent with international assistance. JETP is expected to encourage Indonesia to accelerate the target and net zero emissions by 2050.

Center of Economic and Law Studies (Celios) Director Bhima Yudhistira reminded us that JETP funding is enormous and it is most likely a debt. Moreover, the deals are taken amid the trend of rising interest rates.

According to him, about 60 percent of poor countries are on the brink of default. As for developing countries, according to the IMF, 25 percent are experiencing debt repayment difficulties.

Background

At Glasgow's COP26, developed countries, including the UK, the United States, France, and Germany, announced they would provide US$8.5 billion to help South Africa's transition from coal to clean energy. They call this partnership the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP).

Then, other countries, such as Denmark, the European Union, Norway, Italy, and Ireland, joined. At Germany's G7 summit in June, the group of seven developed economies expressed their support for the concept. The IPG group added Canada and Japan to its list of potential financial backers. Germany also invited Senegal, Indonesia, Vietnam, and India, offering JETP.

IPG's willingness to launch the JETP with Indonesia was negotiated at a meeting in Washington last month. Although at that time, there was still some debate.

Donor countries, for example, ask Indonesia to peak its emissions from electricity in 2030 before reaching zero in 2050-2055. However, Indonesia objected to the schedule.

The government also demanded more funds to speed up the shutdown of coal plants. Meanwhile, donors asked the government to eliminate protectionist policies, coal subsidies, and regulatory uncertainty.

Despite all the debate, the JETP agreement was finally announced at the G20 Summit in Bali.

Stakeholder Statements

Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission:

The Just Energy Transition Partnership for Indonesia will chart a roadmap for a greener and cleaner future in the country – and a future full of opportunities for Indonesian people. They will be the ones reaping the benefits of their economic transformation as Indonesia becomes a renewables hub”

Mafalda Duarte, Head of Climate Investment Fund (CIF):

CIF is proud to support Indonesia on its path from coal to clean power. In Indonesia and across the developing world, the coal transition is a climate imperative and a profound economic opportunity”

Jiro Tominaga, Director of the Asian Development Bank for Indonesia:

JETP is crucial and is Indonesia's victory in this year's G20 Presidency"

Sri Mulyani Indrawati, Minister of Finance:

If developed countries failed to fulfill their promise to fund US$100 billion per year, equivalent to Rp 1,437 trillion for developing countries, then we facing the threat of climate change"

Fabby Tumiwa, Executive Director of the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR):

Every loan has risks. This must be mitigated”

The Insights

Key Points in JETP Deal

Citing the Joint Statement of the Indonesian Government with IPG members in the Indonesia Just Energy Transition Plan, Indonesia and its International Partners announce a commitment to breakthrough climate targets and financing to support an ambitious and equitable energy transition, consistent with the goals of the Paris Accord and contributing to safeguarding the 1.5 degrees Celsius global warming limit.

This commitment also includes accelerating the reduction of the electricity sector's greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050. The strategy is based on the expansion of renewable energy, the gradual decrease in coal-fired power generation, and commitments to regulatory reform and energy efficiency.

Under the JETP, Indonesia must reduce emissions from the electricity sector to 290 million tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) in 2030 before reaching zero in 2050. This is lower than Indonesia's target of 357 million CO2 in 2030 and zero carbon emissions in 2060.

Indonesia must also increase its mix of new and renewable energy (NRE) to 34 percent of its total electricity generation in 2030. This is much higher than Indonesia's target, which is 23 percent in 2025. Until 2021, the Ministry of Energy and Resources Minerals (ESDM) noted that the portion of NRE in the national energy mix has only reached 11.5 percent.

Climate Investment Fund (CIF)

One of the important elements of Indonesia's JETP is the Climate Investment Funds (CIF). Indonesia has long applied for funding from the Accelerating Coal Transition (ACT) program provided by the Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM) program.

CIF head Mafalda Duarte said multilateral development banks and the CIF would account for about a third of the $10 billion public funding for Indonesia's JETP. CIF has allocated about US$500 million to aid Indonesia's energy transition.

CIF is a multilateral fund established to finance climate pilot projects in developing countries. Founded in 2008 at the request of the G8 and G20, CIF manages a collection of programs that assist countries in need to cope with the impacts of climate change and accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy. CIF supports the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Through contributions from 14 donor countries, CIF claims to have supported more than 350 projects in 72 low- and middle-income countries. The CIF partnership has funneled more than US$60 billion from the government and the private sector into projects such as the world's largest solar park, South America's first geothermal power plant, and investments in Mexico's wind power industry.

CIF provides concessional financing accompanied by a grant component. This application is made in collaboration with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank Group (WBG).

On Oct 18, Sri Mulyani sent an official letter and an investment plan to CIF. The letter addressed to Duarte revealed that Indonesia requested around US$600 million in a concessional loan.

These funds will be combined with US$2.2 billion in co-financing from multilateral institutions and US$1.3 billion in commercial co-financing. In addition, there is also a potential contribution from the government worth US$1 billion. In total, Indonesia eyes US$4 billion through this scheme.

"The purpose of this funding is to reduce the excess capacity of energy supply by retiring around 1-2 GW of base load coal-fired power plant within 5-10 years," Sri Mulyani said in the letter.

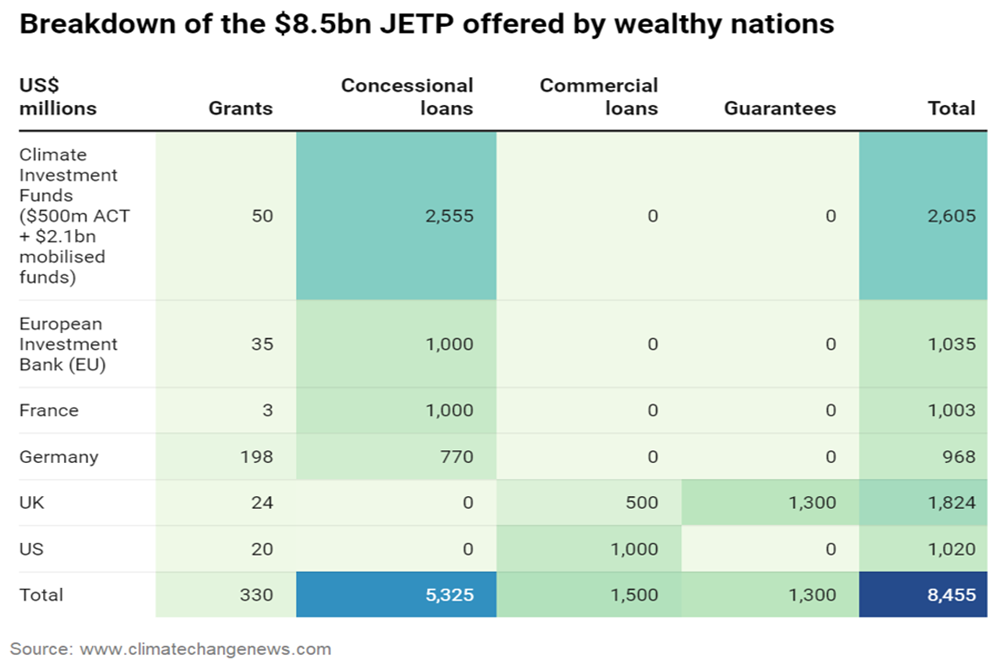

The "Joint Statement: South Africa Just Energy Transition Investment Plan" issued by the European Commission on Nov 7 details the US$8.5 billion IPG initial funding package, including US$2.6 billion through the Climate Investment Fund's Accelerating Coal Transition (CIF ACT); US$1 billion from France; US$1 billion from Germany; US$1.8 billion from the UK; US$1 billion from the US; and US$1 billion from the EU.

"Old Money" or "New Money"?

The cash offer from CIF or JETP combines public and private finance and technical assistance. Indonesia's JETP will raise an initial US$20 billion in public and private financing over three to five years. This financing uses a mix of grants, soft loans, market interest loans, guarantees, and private investments.

The problem is, raising public funds for climate efforts abroad is going to be even more challenging today, even for the world's wealthiest countries. The trend of high inflation, rising energy costs, food crisis, and war in Ukraine have added to the pressure on their finances.

Therefore, for South Africa, many of the investment commitments and funding initiatives provided are "old money" or commitments and programs that existed before the JETP but were later transferred administratively to become part of the JETP.

"The funding commitment from IPG should be new money instead of old money that had commitments before JETP but recycled into JETP funding," Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR) Executive Director Fabby Tumiwa told D-Insights.

Learning from South Africa's experience, the Indonesian government reportedly wants most of the funding commitments in the JETP to be new money instead of commitments from existing programs.

New Debt Trap?

Most of the JETP funding that South Africa gets is debts. Around 97 percent of these funds are loans, and only three percent are grants. Indonesia's JETP scheme is still under discussion for the next six months. But most of the funding commitments provided are likely debt. It would be very difficult to expect Indonesia to receive a grant of up to ten percent of the JETP funds.

Half of this amount of US$10 billion will be collected from IPG members. The EU, part of the IPG, will mobilize around US$2.5 billion. The 27-country union will support a partnership through the European Investment Bank (EIB) with €1 billion to support eligible projects that contribute to the decarbonization of Indonesia's electric power system through the development and integration of renewable energy. The EU will only allocate €25 million in grants and technical assistance.

Meanwhile, the UK supports Indonesia's JETP program, including through a US$1 billion World Bank Guarantee. The facility will allow Indonesia to increase its lending rate under World Bank terms to US$1 billion.

The remaining US$10 billion is in private investment from an initial series of private financial institutions coordinated by the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), including Bank of America, Citi, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Macquarie, MUFG, and Standard Chartered. The partnership will also leverage the multilateral development bank's expertise, resources, and operations.

Although it will add new debt, Fitch Ratings is optimistic that Indonesia has greater fiscal financing flexibility for energy sector investment than South Africa. If a JETP agreement pushes public debt or spending higher than it should be, this can weigh on a country's credit profile, depending on the scale and nature of the program.

"We see a significant possibility for JETP to reduce financing costs for projects that will be continued. This would be a positive credit, but the impact may be small," FitchRatings wrote in its research (11/11).

Donor Countries May Step Back from Commitments

JETP supports developed countries to help developing countries reduce their dependence on fossil fuels such as coal and gas, which causes carbon emissions that contribute to climate change.

At the 2009 United Nations Climate Summit in Copenhagen, developed countries committed to providing at least US$100 billion by 2020 to help developing countries tackle the challenges of climate change. This financial assistance is also compensation for developed countries which are the biggest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, and poor and developing countries feel the impact. However, years have passed, yet they still have not fulfilled that commitment.

If the commitments of these developed countries are fulfilled, there should be more grant schemes in JETP financing. At least half of the financing that IPG collects is a grant because it is challenging to expect grants from the private sector (GFANZ).

Indonesia May Also Backslide from Commitment

Indonesia can also backslide from commitments. During the discussion, the European External Action Service (EEAS) reported that the agreement brokered by the US and Japan with Indonesia was on the brink of cancellation.

The reason is that Presidential Regulation (Perpres) No. 112/2022 still legitimizes and secures the construction of coal-fired power plants in the pipeline. In fact, the government has agreed to retire coal plants of up to 5 gigawatts.

Because of this, the EEAS report says that talks have deteriorated on these aspects: "Indonesia is starting to deviate from its previous constructive position on necessary policy reforms."

The new Energy and Renewable Energy Bill discussed in the House of Representatives must also conform to the JETP agreement. The current government has not submitted the Problem Inventory List (DIM) related to the bill until the deadline ended last month because it was waiting for the JETP agreement. The carbon tax implementation, which was supposed to start this year, was delayed until 2025.

However, if the provisions in the bill are not pleasing to the donor countries because they give contradictory signals, the funding commitments can be revised.

IPG and Indonesia have agreed on a partnership action plan within six months regarding the detailed funding planning. Indonesia must also be transparent in the use of its funds. If the funding commitment is not under the principle of justice in the first six months, it can be revised.